In the past two years a variety of books on the Arab revolutions have appeared in English. They range from "instant histories" based on tweets to the accounts of journalists who covered the uprisings.

The book Writing Revolution: The Voices from Tunis to Damascus published recently in London by IB Tauris is different from other books so far on the Arab revolutions. It is a unique collection of substantial essays on the revolutions by eight authors from different Arab countries (excerpts are on the IB Tauris website). All but one of the essays were completed between May and December 2011. Wishful Thinking by Saudi journalist Safa Al Ahmad is dated September 2012.

The essays were specially commissioned by the editors: activist and writer Layla Al-Zubaidi, who is Director of the Heinrich Böll Foundation in South Africa and was previously based for the Böll Foundation in Beirut and Ramallah; journalist and photographer Matthew Cassel, who covers the Middle East for Al Jazeera English and is former Assistant Editor of The Electronic Intifada; and literary agent and writer Nemonie Craven Roderick .

The introduction to the collection is by the renowned Syrian writer, journalist and activist Samar Yazbek. In 2012 Yazbek won the PEN Pinter International Writer of Courage prize, and the PEN Tucholsky Prize in Sweden, for her book A Woman in the Crossfire: Diaries of the Syrian Revolution (Haus, 2012). This year she won the Oxfam Novib/PEN Award for Freedom of Expression.

Yazbek writes: "These revolutions pre-empted the process of revolutionary and intellectual theorizing, and yet now wait on a new form of literature to describe them: a writing forged in the present moment." The essays "vary between the personal and the general, but all express a single point: that writing at a time of revolution is part of the process of change. Moving between the subjective and the dispassionate, they offer us examples of heroism and of hope for the future."

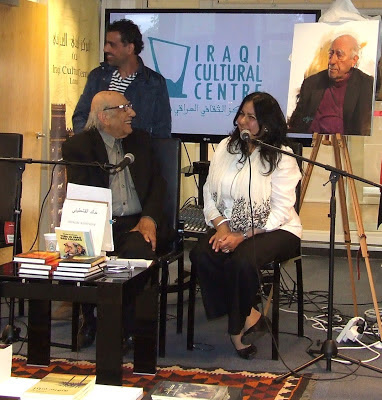

L to R: Matthew Cassel, Layla Al-Zubaidi, Nemonie Craven Roderick and Mohamed Mesrati

At an event on Writing Revolution at the Mosaic Rooms in London, Nemonie Craven Roderick said: "I don't think it's inappropriate to invoke Walter Benjamin who, when he felt there was a need for a new kind of historical writing, said it should be by those who can bear witness to change at a moment of risk or danger. That's what the contributors to this book have done, and the essays are incredibly striking. They are certainly very personal, and passion really flies off the page."

The excellence of the book was recognised when it won an English PEN Writers in Translation Award 2013 last November. The awards provide publishers with funds to promote and market the winning books.

Craven Roderick said it is hoped that, following its publication in English, there will be various foreign editions of Writing Revolution. It already has a Turkish publisher, Metis, which was co-founded by "an amazing courageous publisher Müge Sökmen - a wonderful woman." She added: "We are in conversation with a few Arabic publishers."

The evening at the Mosaic Rooms was one of several UK events to mark the launch of Writing Revolution. There were events at the Hay Festival,with English PEN's director Jo Glanville; at the Frontline Club in London, chaired by journalist and writer Rachel Shabi; and at St Anne's College, Oxford University, organised by Oxford Student PEN.

On 28th June there is an opportunity to hear contributors Mohamed Mesrati of Libya and Malek Sghiri of Tunisia when they appear at The Rich Mix in London as part of the Shubbak Festival of contemporary Arab culture.

At the Mosaic Rooms Mesrati appeared alongside the book's editors. Layla Al-Zubaidi said: "For us the aim was to get out some of the voices that usually wouldn't be translated: some of the authors have never been translated into English and some have never written anything, even in their own languages."

She said that although journalism and the activities of foreign reporters have been important, "we felt that it's also important to hear people who are actually engaged in the revolutions writing about themselves in their own language. We wanted them to write in a literary fashion so that we wouldn't have the same as is found for example in blogs or newspapers."

Craven Roderick highlighted the vital role of translator Robin Moger, who translated five essays and Yazbek's introduction from Arabic to English. She noted that Moger is also translating Mesrati's novel-in-progress Mama Pizza and his other work, and is "incredibly excited" about his writing.

Algerian journalist Ghania Mouffok wrote her essay We Are Not Swallows in French; it was translated to English by Georgina Collins. Safa Al Ahmad and Egyptian journalist and writer Yasmine El Rashidi submitted their contributions in English.

Al-Zubaidi said the editors had wanted to make sure that the contributors were really honest about their weaknesses and doubts: "If you read the essays you can read a lot of doubt and sometimes also fear about the future. We felt it is extremely difficult in that milieu to find people who really express themselves very honestly... we didn’t want to have political messages, we really wanted to have personal stories with all their kind of conflicting identities, opinions etc."

Matthew Cassel pointed to the limitations of journalism, with journalists having to meet limits such as word count and deadlines, and increasingly relying on "a small number of elite experts who have made a career out of analysing events in the Middle East."

He said: "That's exactly why I think we need more voices who at least couple the journalism with the voices on the ground to really give us the depth, the detail about what’s happening on the everyday. If we just follow the news we’re not really going to get a full picture of what’s happening in these countries."

The Mosaic Rooms event was enhanced by readings from Writing Revolution by actors Sam West and Jonjo O'Neill. Belfast-born Jonjo O'Neill read from Mesrati's essay Bayou and Laila in his warm Irish accent. Sam West gave a powerful reading from Bahraini activist, critic and author Ali Aldairy's essay Coming Down from the Tower.

Mesrati completed his wide-ranging essay in exile in London in May 2011 while the Libyan revolution was raging, its outcome far from certain. He said: "When I wrote it I thought it was going to be the last thing I'm going to write, because at that time I was going back to Libya."

Nemonie Craven Roderick and Mohamed Mesrati

Bayou and Leila is named after Mesrati's parents, opponents of the late Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. They fled Libya with their children in 2005 and were eventually given asylum in the UK. Mesrati was 21 when he wrote his essay. At the time he was beginning to make a name for himself as a writer of short stories, and an excerpt from Mama Pizza had been published in April 2011 in Banipal 40's special feature on Libyan Fiction (Mesrati talked about his life and writing in this interview).

Knowing the essay might be his last-ever piece of writing, Mesrati tried "to deliver many messages - to tell the story of my parents in opposition, and to tell the story of my friends, and to say what I wanted to do in this life, and what I wanted to write, and all the dreams that I wanted to come true - but there was only one thing I had to do, to go back there and be among all the rebels and join the fighters." He felt he needed to put into the essay "all the novels I'd like to write in the future, and all the essays".

Mesrati's wide-ranging essay begins with his being "born into history" in Tripoli in 1990, when Libya was suffering under the sanctions imposed after the Lockerbie bombing. With humour and precision he conveys the flavour of life as a child growing up under the Gaddafi regime as part of "a generation born from our fathers' defeats." In art classes pupils would illustrate "tragic and deeply dull themes like 'Spring', 'The Joy of the Libyan People at the Revolution', or 'Cleansing the British camps from the Homeland's Soil'. Not once were we asked to draw a loved one's face or our parents."

He and his four deareset friends Khairi, Altakali, Baaisho and Faris got up to mischief and played schoolboy pranks. But there were undercurrents of fear. Mesrati's father was an actor and theatre producer, but the regime's repression, censorship and paranoia severely curbed artistic freedom. He earned his living working in the oil industry.

Young Mohamed's favourite childhood story was The Elephant, O Ruler of Time! which his father would tell him with "his rich radio voice and his theatrical gestures." Only some years later would Mesrati fully grasp the desperate truths about Libya and its ruler Colonel Gaddafi symbolised in the story.

Jonjo O'Neill

Mesrati's essay takes a chilling turn when he depicts the horrific days when his student father and schoolgirl mother witnessed the terror of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Students were crushed and some were publicly hanged.

When the Libyan uprising started on 15 February Mesrati re-established from the UK contact with his childhood friends Khairi, Baaisho and Altakali in Libya (Faris had been killed in a car crash). He received daily reports from them which he circulated on Twitter, Facebook and elsewhere. The three friends went to fight for the revolution. On 21 February 2011, "the day of sadness, the day the cross of tears was lowered across my back", Mesrati learned that they had been killed.

Mesrati's essay concludes: "This story doesn't end here. The truth is that there are many stories that need to be told ... this is a people that have borne the weight of enough stories to fill all the novels and films you could wish for. To be continued..."

Mesrati is now working on a film, The Morganti Rebels, with Lebanese director Nisrine Mansour. The film tells of four friends who were on the frontline during the revolution and launched a coffee shop in the heart of Misrata. "They have a library and they are doing gigs every Thursday and they have literary events and a place for discussions. Many intellectuals, writers and activists after the war started to go regularly to that coffee shop. We would like in this film to focus on art activism in Libya after the war and how culture and art are the only things that can make a change in society."

Ali Aldairy participated in the uprising in Bahrain but now lives in exile, founding the online Arabic newspaper Mira'at al-Bahrain (The Bahrain Mirror). He was unable to attend the UK launches of Writing Revolution, but at the Frontline Club event he was represented by his friend and fellow Bahraini activist Ali Abdulemam. Abdulemam was one of the first to agree to contribute to Writing Revolution, but he then went into hiding for two years and the book's editors lost touch with him. He was sentenced in absentia to 15 years in prison and recently fled from Bahrain to the UK where he has been granted political asylum.

Aldairy gives a vivid account of participating in the uprising, which was met with violence by the security forces. He writes that the Bahrain revolution is about two things: state and sect. "How does a sect make the transition to a state? How does the state become a system of governance capable of incorporating a number of sectarian gropus with different (if not openly contradictory) cultures, interests and historical narratives?"

He recalls the funeral on 18 February 2011 of engineering student Ali Ahmad al-Mumin, shot in an attack by security forces on Pearl Square. Al-Mumin's final entry on his Facebook page was: My blood for my country. "Six hours later his words became reality, a truth that stunned his father, mother and six siblings when they received news of his martyrdom." Looking at al-Mumin's Facebook page "my senses were penetrated by his glowing image. I sat frozen before the picture: from its depths something was calling me to write about him."

Aldairy wrote an article for an-Nahar, addressing the dead student. "I see you in every young man I met" he wrote. University students copied the article and made it into a booklet which was distributed in Pearl Square. Aldairy was overwhelmed when Al-Mumin's father phoned him, and when later on he met the student's brother.

Sam West

Saudi journalist Safa Al Ahmad writes perceptively of her visits to Arab countries in the throes of revolution, intercut with highly critical observations on Saudi Arabia. She begins: '"I'm Saudi. I'm sorry.' It's a phrase uttered at every introduction in Tunisia, Egypt and Yemen, not so much in Libya. Whisper it to myself in Bahrain." Sitting with Yemeni women who are discussing revolution she feels they are decades ahead of Saudi Arabia on women's rights and civil society. In her Cairo hotel room she experiences "full-on revolution jealousy and depression".

Layla Al-Zubaidi said that in their essays the contributors to Writing Revolution reflected on their own roles and "described what has led up to the revolutions so that people realise the revolutions didn't actually fall from the sky." The contributors had already invested much time and energy in political change before the uprisings began.

The Tunisian activist, trade unionist and student leader Malek Sghiri is from a long line of activists: his father was a political prisoner for a total of seven years under the Bourguiba and Ben Ali presidencies. In Greetings to the Dawn: Living Through the Bittersweet Revolution he writes of how during the revolution he and his comrades were horribly tortured at the Ministry of the Interior. His interrogator told him: "In 1991, inside this building but in a different room, I was one of those who interrogated your father."

Egyptian journalist and author Yasmine El Rashidi writes in Cairo, City in Waiting of leaving her grandmother's Cairo house, in which she had grown up, to go and study in the US in 1997. On visits back to Egypt she saw Cairo becoming "downtrodden and dim". In summer 2010 she realised something was shifting, and later she was an eye-witness to the revolution: "... my memories of the 18 days, the revolution, are mere fragments of a larger journey and search that I now wait to complete."

Matthew Cassel and Layla Al-Zubaidi

Jubran has endured a series of vicissitudes, personal and political. After the unification of Yemen in 1990 he worked for a socialist newspaper. Then in the disastrous civil war of 1994 the Socialist Party was defeated. He eventually became a lecturer in the French department of a university, but then found his name on a hit list of an extremist party's "enemies of Islam". He became emboldened by a group of young journalists who championed honest writing and freedom, and in his articles he expressed in particular his anger at the prospect of president Ali Saleh passing power to his son Ahmed. Around the time students started to demonstrate for the removal of the president, Jubran was dismissed from his post at the university.

When the "Arab Spring" reached Yemen Jubran found it painful that certain Arab writers and intellectuals "found it hilarious that such a thing should be attempted in Yemen, and regarded our young people as poorly equipped for a revolution when compared with their contemporaries in Tunisia and Egypt." Many were killed but "we did not fire a single bullet in response." He lost many of those he knew and feels bad about not joining the demonstrators in the revolution. "I did nothing but write."

Algerian journalist Ghania Mouffok's essay We Are Not Swallows is a reminder of Algeria's painful history. "This epic has gone on for 130 years" she writes. When she takes her son on demonstrations "it's not to teach him anything, but to show him that being a citizen of Algeria can be joyous, chaotic and rebellious." Her essay has an elegiac tone. She writes: "We are not swallows. We're not just making spring but also winter, autumn and summer too, because we've been around for a long time."

Khawla Dunia is a Syrian lawyer, writer and researcher and a member of the editorial board of the Damascus Center for Theoretical Studies and Civil Rights. She is the author of several studies, and contributes to the Arabic website Safhat Suriya. And like Yazbek she is one of those Alawites (the sect to which President Bashar Assad belongs) to take a courageous stand for freedom.

Dunia's essay, an account of the uprising in its first 100 days after the killing of demonstrators in Deraa, has the apt title And the Demonstrations Go On: Diary of an Unfinished Revolution. As Misrati does with Libya, she compares Syria to the republic of fear portrayed by George Orwell in his novel 1984. Her husband had already been imprisoned twice previously for his political activities, and he is arrested for a third time during the uprising. He suffers brutal torture in detention, its marks obvious when he is released on bail.

Dunia's words "where is the country heading? The future is is terrifying and obscure" are, unfortunately, as apposite today as when she wrote them.

report and photos by Susannah Tarbush