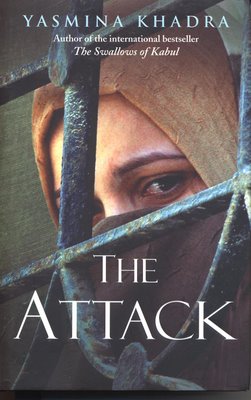

In the Country of Men

by

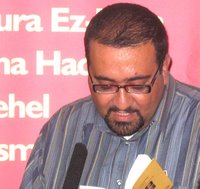

Hisham Matar

Viking, London, 2006

This first novel by the Libyan writer Hisham Matar, who has lived in London for many years, has generated much excitement in publishing circles. The Bookseller hailed it as “the most highly prized literary debut of the autumn.”

Within a week of Matar’s literary agent submitting the novel to publishers, it was the subject of a highly competitive auction in the UK. The auction was won by the Penguin imprint Viking, which gave Matar a two-book deal. There were also auctions abroad, and the rights to the book were sold in 14 countries prior to publication.

The novel does not yet have an Arab publisher, but Matar regards the Arabic translation as “without a doubt the most important one for me out of all the translations.” The novel is currently being translated by the London-based Iraqi short story writer and literary critic Luay Abulilah.

Matar says: “I think he’s done a very good job; he’s managed to get under the skin of the language. The language is deceptively simple, but it’s got tones and colours and there’s something sensuous about it.”

Viking’s editorial director Mary Mount, editor of the novel, rates it as “a very rare find…the sort of book that makes publishing worthwhile.” Matar is “a very serious writer who puts an enormous amount into his writing” and editing with him was a “wonderful experience.” In her view he has “a huge future as a writer”.

Some novels fail to live up to their pre-publication publicity, but In the Country of Men fully deserves the accolades it received before publication from novelists of the calibre of JM Coetzee, Nadeem Aslam and Anne Michaels.

Matar has produced an accomplished and moving novel, at once accessible and mysterious. It is a literary novel, yet intensely readable. He has written poetry for much of his life, particularly focusing on it since the mid-1990s, and his gift for language is much in evidence in his prose.

In the involving, many-layered narrative, the first-person narrator Suleiman looks back to his nine-year-old self trying to make sense of the confusing family and political events that whirled around him in Tripoli in summer 1979, “that last summer before I was sent away”.

The novel is expertly paced, and the tension builds to an almost unbearable pitch as the net closes around Suleiman’s father and his associates, who are linked to a student democracy movement.

In the book’s concluding section Suleiman, now 24 years old, tells of the fifteen years that have elapsed since his parents sent him into exile in Cairo. Although he integrated quickly into Egyptian society, “I suffer an absence, an ever-present absence, like an orphan not entirely certain of what he has missed or gained through his unchosen loss.”

Matar was born in New York in 1970 to a diplomat father, and lived in Tripoli between the ages of three and nine. In 1979 the family was forced to leave Libya and moved to exile in Egypt after his father was threatened with interrogation and arrest during a crackdown by the regime.

Much worse was to come. In March 1990, while Matar was at school in England, his father Jaballah disappeared from the family home in Cairo. It is assumed that, like several other Libyan dissidents, he was abducted and handed over to the Libyan regime. To this day, despite representations to the Libyan leadership and the taking up of the case by human rights groups including Amnesty International, Matar and his family do not know whether his father is alive or dead.

Matar stresses that his novel is not autobiographical, although it is permeated by a sense of loss, exile and ambiguity. Nor does he see himself as a political writer. Rather, he is concerned with “how people change over time, how circumstances alter the human heart.”

Matar set the novel in Libya because of his interest in “certain themes that are very much to do with Libya. And I also feel that as far as the literary voice of Libya is concerned, it’s not a very vocal voice. It’s a silent country – at least that’s the impression the world has, I think with good reason.”

He adds: “The kind of literature that stands the test of time is the kind of literature that comes out of urgency, that comes out of a sense that it has to be written. In a way the book writes the author, and that kind of book doesn’t come by choice.”

The novel is intricately structured, but Matar did not start out with a plot outline. For him writing is exploration, and “what determined the structure was the voice. The voice really intrigued me, and it is what kept me interested and committed. It kept nagging at me.”

Matar spent the first phase of work on the novel trying to meet the technical challenges of writing in the voice of a nine-year-old. “What does it mean to be nine years old? How do you perceive the world? There is something quite unique about children, the present seems eternal and there isn’t really any experience of time passing. In many ways it’s quite a positive thing because a lot of them live in the moment and their living experience tends to be extremely intense.”

One theme running through the book is Suleiman’s anxiety over questions of masculinity and what it is to be a man. Suleiman is an only child, and when his father is away on business trips he is forced to become the man of the house and to look after his mother. She drinks the “medicine” (illicit grappa) that she covertly obtains from the local baker, and when she is drunk, or “ill” as Suleiman interprets it, she uses her son as the sounding board for her dissatisfactions. She recalls that “black day” when she was forced by her brothers to get married to a stranger at the age of only 14 after she was seen in a café drinking coffee with a boy.

Matar charts the boy’s ambivalence towards his mother. “I remembered the words she had told me the night before, ‘We are two halves of the same soul, two open pages of the same book,’ words that felt like a gift I didn’t want.”

In the novel’s opening scene Suleiman has been told that his father is away on business, but during a shopping trip with his mother he glimpses him in Martyr’s Square followed by his office clerk Nasser carrying a typewriter. His father enters a building, and Suleiman sees him at a top floor window hanging a small red towel on the clothesline.

The father is a rather distant figure; Suleiman wishes his father could be more like Ustath Rashid, his father’s best friend, or Moosa`, the Egyptian judge’s son who provides Suleiman with friendship and affection.

On their way home, mother and son are followed by a car carrying four men in dark safari suits. “I remembered so suddenly I felt my heart jump. They were the same Revolutionary Committee men who had come a week before and taken Ustath Rashid.”

Suleiman witnesses Ustath Rashid’s televised “confession”, summary trial and hanging in a sports stadium in front of a hysterical cheering mob. The televised execution of Ustath Rashid “… would leave another, more lasting impression on me, one that has survived well into my manhood, a kind of quiet panic, as if at any moment the rug could be pulled from beneath my feet.”

The novel depicts a society of informers and mukhabarat, where leaflets criticising the Revolutionary Committees circulate overnight, and where telephones are crudely tapped.

The world of boys and their games runs parallel to the adult world. Matar’s best friend Kareem is Ustath Rashid’s son and the arrest of Ustath Rashid affects the dynamic between the boys. Suleiman is caught up in betrayals and complicities and experiences the fleeting pleasures of the misuse of power.

The mother and Moosa burn the father’s books in order to protect him, but Suleiman hides one of the books. After the father is seized, the mother makes a humiliating appeal for his life to a neighbour who is a senior member of the mukhabarat. When Suleiman’s father returns home from his brutal ordeal, he and the mother draw closer and find a new mutual need and passion which tends to shut out their son.

After Suleiman is sent alone to live in Cairo, a series of decrees in Libya ruin his parents financially and his father goes to work in a pasta factory. Suleiman finds the Libyan embassy has a file on him as an “evader” because he has not returned for military service. When he is fourteen a decree is issued warning that all “Stray Dogs” who refuse to return will be hunted down. His parents are refused a visa to leave the country, “holding them hostage, as it were, until the evading Stray Dog returned.”

Suleiman asks: “Why does our country long for us so savagely? What could we possibly give her that hasn’t already been taken?”

In the Country of Men has a transcendent quality that lifts it above its often harrowing subject matter. As an adult, Suleiman learns what became of the people he knew as a child in Tripoli, and how they have adapted to their situation. The novel ends on a note of gentle and hopeful resolution.

Susannah TarbushUnedited version of review published in Banipal magazine No 26, Summer 2006